When a bleary-eyed sub-editor in a cramped Lagos newsroom clicked publish on an AI-generated headline about a missing schoolgirl in Anambra, he probably sighed not from pride but from exhaustion. He had probably spent all the night to watch how algorithms outpace his own thinking, trim sentences, optimise keywords and predict virality better than he ever could. In the end, he simply gave in to the reality that technology has rewritten the rules of media production, and the paradigm shift may be here to stay.

Although it sounds unrealistic, I sometimes wonder how Nigerian newsrooms would survive without AI. I would have loved to hear the old protests that “AI is not a journalist’s tool.” But those voices are fading fast. During my data collection at Daily Trust in Abuja, only one reporter still claimed he would never use AI. The rest had surrendered to its convenience. The irony is now tender and worrying. The reporter who once feared being replaced by AI now imitates its speed, mimics its tone and begins to measure truth not through empathy but through engagement analytics.

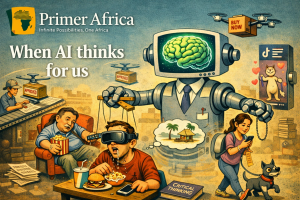

Automation entered journalism as a friendly assistant with data-heavy tasks. Algorithms wrote financial summaries and generated sports updates. Many journalists ignored the change at first. But data is never neutral. Each automated sentence slowly reshapes how the newsroom thinks. Reporters begin to ask not why a story matters, but how well it will perform. Like Narcissus gazing into the pond, journalism risks falling in love with its own reflection in the algorithmic mirror. In Nigeria, the shift is visible across different outlets.

According to the Reuters Institute Digital News Report (2025), AI adoption is gaining traction in Nigerian newsrooms, with tools being used for tasks such as copyediting and content illustration. Some newsrooms experiment with automated transcription to speed coverage of breaking events. Smaller digital platforms test auto-generated social captions to keep up with demand. The temptation is obvious. Budgets are tight, expectations are high and the chase for traffic is relentless.

This raises difficult questions about the meeting point between AI and journalism. When AI learns from journalists, does it also inherit their bias? When journalists borrow from algorithms, do they lose their instinct for human feeling? The tension is sharp because today’s newsroom demands both the precision of data and the warmth of emotion. Nigerian journalists carry a heavier load. They must fight for space in a noisy digital world while reporting local stories that cut deep into people’s lives. Picture a correspondent covering the recent Free Nnamdi Kanu protest in Abuja. An AI tool can count hashtags, track crowd movement and summarise speeches. But it cannot feel the tension that rises when police sirens echo down the street, or hear the quiver in a mother’s voice as she clutches her son’s photograph. Only a human can turn those sensations into words that move readers.

The danger comes when the hunger for speed overtakes the duty to understand. When clicks matter more than truth, journalism begins to lose its soul. Stories become headlines that are built for traffic, not meaning. Facts are repeated without reflection, and emotion fades into templates of convenience. What was once a mirror of society becomes a machine that simply records sound without hearing it.

Yet hope still lives in the newsroom. AI and journalism do not need to fight for space. They can work together. The machine can take on repetitive jobs such as transcribing long interviews, scanning thick reports or sorting through endless data. The journalist can do what the machine cannot do which is to verify each claim, ask uncomfortable questions and give feeling to the facts. The strongest newsroom is the one where AI sharpens the tools and humans guide the purpose. The journalist who knows when to lean on the algorithm and when to step away from it becomes something rare, a thinker who blends skill with conscience and speed with reflection.

In practice this means using AI as support and not substitution. Let the software trace numbers, detect unusual patterns and point out new angles. Let people read motives, test every claim and sit with those whose stories shape the news. A reporter who forgets doubt, empathy and conscience is no longer a journalist but a recorder. And if AI learns from us long enough it will copy not only our intelligence but also our flaws. That is a truth we must face with clear eyes.

Perhaps journalism and AI are two sides of the same hunger, both searching for truth and both blind in different ways. The real danger is not that machines will learn to think like journalists but that journalists will start thinking like machines. In a world where algorithms can write headlines and bots can draft full reports, the bravest act left for a journalist is to remain human. To pause before publishing, to feel before phrasing, to let conscience shape the story. Without that human touch, journalism loses depth, meaning and heart.

Azeez Sulaiman is a writer, analyst and AI researcher. He recently completed his Bachelor of Science in Mass Communication at Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. His final year research explored the intersection of generative AI and the modern Nigerian newsroom, focusing on Daily Trust and The Guardian. He can be reached via email at azeezsulaiman05@gmail.com or by phone at 0813 354 6108.