|

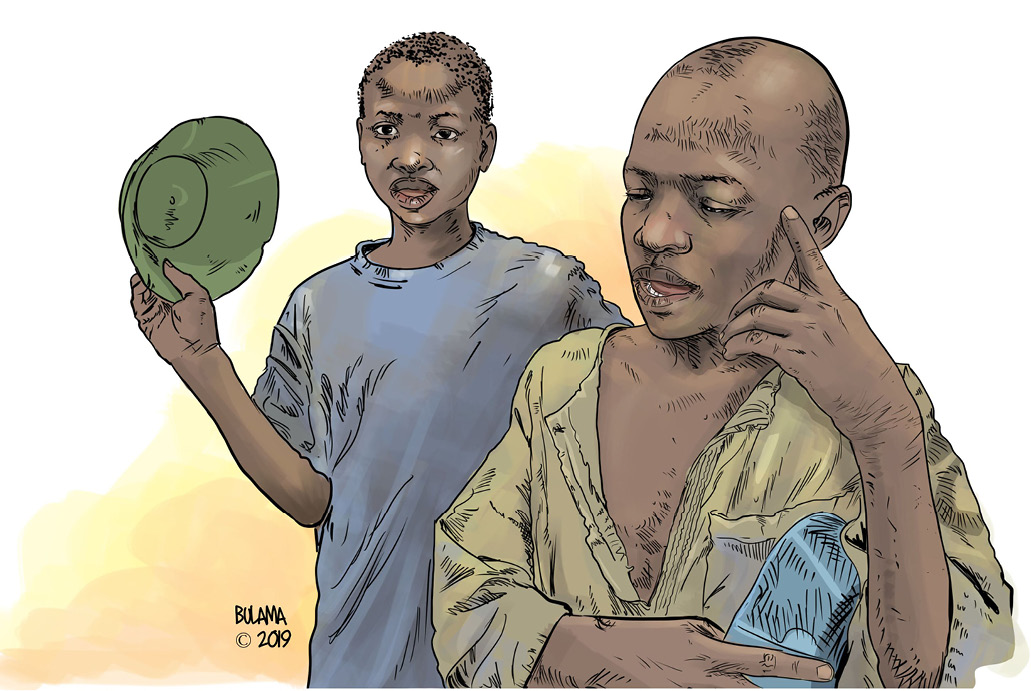

| A painting of the Almajiri kids, Credit: Bulama (2019) |

The tale of the Talibes or the Almajiri child illustrates the harsh realities of marginalized youth in Senegal and Northern Nigeria who face several obstacles in the Tsangaya and Daara school systems. This article explores the significant and pervasive struggles these kids experience, illuminating the social, academic, and financial challenges they face.

Who are the Almajiri(s) or Talibe(s)?

The term Almajiri, which translates to “apprentice” in English, refers to a group of migrants or errant children who left the comfort of their homes and families in search of Islamic education in the Qur’anic school known as “Tsangaya” through a process known as “Almajiranci.” Almajiranci is an Islamic education system utilized in northern Nigeria. This practice is also prevalent in major cities throughout Senegal, including Dakar. Unlike in Nigeria, these children in Senegal are known as Talibes, which translates to “students” in English. The Talibes, like the Almajiri children, leave their homes at relatively young ages ranging from 4 to 15 in search of Quranic knowledge. Although these customs extend back to antiquity, their function in today’s society has been defeated, and these systems have become only a reflection of the poverty that plagues the Sub-Saharan African region. This problem has been discussed in numerous journals and blogs, but little has been done to put an end to this practice.

Consider how it feels going out to eat at a restaurant and finding a bunch of shabby and frail-looking young kids begging for donations in order to get their next meal, that was a brief highlight of my experience living in Northwestern Nigeria. These children are neglected and permitted to walk freely during the day and night, with no safe place to sleep. While there are numerous explanations for this unfavorable and unsightly habit, the primary culprits are poverty, a lack of sufficient education, and traditional beliefs. The practice of the Tsangaya or Daara system threatens the social and security well-being of their host countries in the near future, so we feel compelled to draw attention to it by discussing it on our blog. We believe that by investigating the limitations of the Tsangaya and Daara systems and their impact on these vulnerable children, we can begin to address the urgent need for reform and greater possibilities for their holistic development:

1. Lack of Access to Quality Education:

One of the most pressing concerns for Almajiri and Talibe children is a lack of access to high-quality education. The Tsangaya and Daara system, which has traditionally been in charge of Quranic education, frequently fails to provide a comprehensive curriculum that includes key disciplines such as mathematics, science, and reading. As a result, Almajiri youngsters lack the requisite abilities to negotiate an increasingly competitive market, limiting their future employment and socioeconomic progression opportunities. They end up negatively contributing to the nation’s overall economic growth and the security well-being of their host towns; these consequences are quite terrible for an area that is already facing difficult challenges. According to UNICEF, around 9.5 million children in Nigeria are out of school, with Almajiri children possessing a sizable part. This figure is extremely concerning and requires immediate intervention before it becomes uncontrollable.

2. Social and Economic Vulnerability:

The suffering of the Talibe and Almajiri children goes beyond education. Many people are stuck in a cycle of poverty and vulnerability, with little access to basic healthcare, nutrition, or social support systems. Living conditions in overcrowded and filthy Tsangaya and Daara schools contribute to illness transmission and expose students to a variety of health concerns. Furthermore, the lack of occupational training and skill development limits their economic self-sufficiency potential, creating a cycle of marginalization.

3. Stigmatization and Discrimination:

Almajiri children are frequently stigmatized and discriminated against in society. The impression that they are only involved with begging or committing minor crimes contributes to unfavorable perceptions that impede their integration and social acceptance. Such attitudes exacerbate Almajiri children’s marginalization and hinder their possibilities for upward mobility.

4. Exploitation and Vulnerability to Radicalization:

The Daara and Almajiri children are vulnerable to exploitation and manipulation because of their terrible conditions. Some unscrupulous people take advantage of their weaknesses, forcing them to work as children, beg on the streets, or engage in illegal activities. Furthermore, a lack of sufficient guidance and supervision exposes them to the potential of recruitment by extremist groups, increasing the region’s security issues.

Need for Comprehensive Reforms:

To address the plight of Almajiri children, significant cultural reforms within the Tsangaya and Daara systems are required. Grassroots initiatives must concentrate on educating parents, community leaders, and neighborhoods about the consequences of these heinous practices. There is also a need for improved and integrated educational practices that include both Western and Islamic education to ensure that young males are adequately taught to be self-sufficient in the future. Collaboration between the government, civil society organizations, community, and religious leaders is also critical in providing holistic support to vulnerable individuals in underserved communities, including healthcare, nutrition, and psychosocial services. Furthermore, quality and comprehensive vocational training programs can provide these young children with vital skills as they get Islamic education, allowing them to obtain livelihoods and break the cycle of poverty.